KYOTO, Japan — Every week, 62-year-old Miyuki Tanaka joins a pious crowd of Buddhists heading to the historic Kodaiji Temple in Kyoto, Japan.

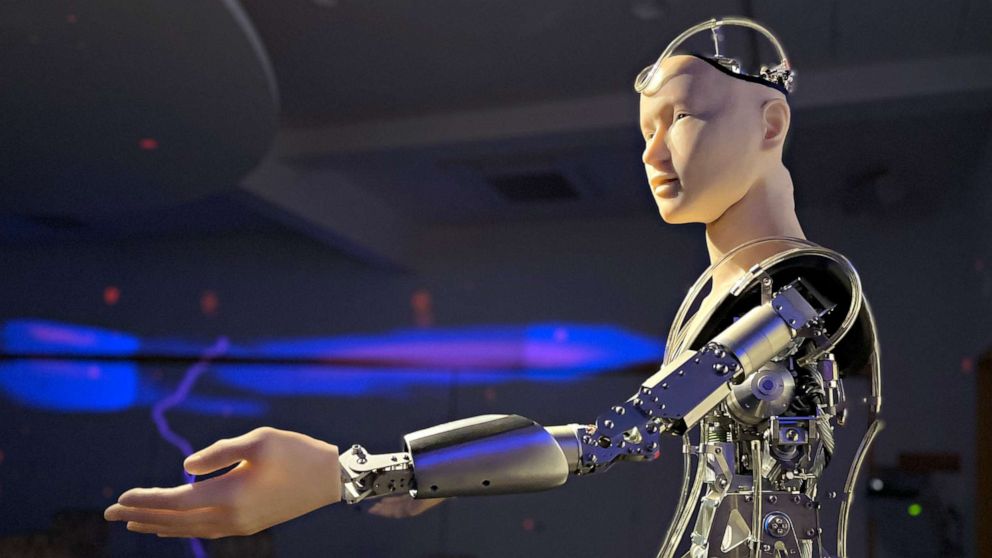

Inside the temple stands Mindar, a 6-foot-4-inch, 132-pound priest. With charismatic hand gestures and a piercing gaze, Mindar delivers a poignant sermon on one of the most-read Buddhist scriptures, the Heart Sutra. The sermon is indistinguishable from the one given by the usual priest — until visitors notice Mindar’s smooth silicone skin, aluminum bones and camera-embedded eyes.

In this historic temple, Buddhists learn the teachings of Buddha from a humanoid, the robotic embodiment of the Buddhist goddess of mercy, Kannon.

“I often experience mood swings, taking care of my elderly mother. Mindar’s sermons on the Heart Sutra help me control my emotions and bring salvation,” Tanaka told ABC News.

In a country where two-thirds of the population identify as Buddhists, Tanaka is only one of the many with whom Mindar’s sermons have resonated.

Visitors at Kodaiji Temple listen to sermons from Mindar in Kyoto, Japan, June. 11, 2022.

Kodaiji Temple

“Before listening to its sermons, worshippers view Mindar as a robot. But after, they perceive it as Buddha, not a robot,” Kodaiji Temple’s chief steward, Tensho Goto, told ABC News.

Mindar was born in 2019 from a $1 million collaboration between Kodaiji Temple and a team led by Professor Hiroshi Ishiguro from the Department of Systems Innovation at Osaka University. Their goal was to enhance spiritual experiences and revive interest in Buddhism, which has been dwindling due to modernism and generational change in Japan.

The design of the humanoid seeks to bridge the gap between the spiritual world, where Buddha exists, and the physical world, where Buddha’s form materializes through Mindar, according to its creators.

The camera lens in Mindar’s left eye enables eye contact with worshippers. Its hands and torso move to imitate human-like interaction. The humanoid’s “gender and age-neutral look” also encourages worshippers to conceive their own image of Buddha.

Mindar folds his hands to pray in Kyoto, Japan.

Kodaiji Temple

“The design policy for Mindar was about encouraging people’s imagination. Buddha’s statue has a similar design: it’s difficult to see the statue’s age and gender,” Ishiguro, who designed Mindar, told ABC News.

Also complementing the robot’s design is an interactive 3D projection mapping where videos of worshippers are displayed on the wall behind Mindar. In a pre-programmed presentation, a person projected onto the wall asks questions about Buddha’s teachings to Mindar, which replies with lucid explanations. The technology invokes the sensation that worshippers coexist in a non-physical, parallel reality with the Buddhist deity.

Although Mindar’s abilities are limited to citing preprogrammed sermons at the moment, the temple has plans to introduce additional features.

“We plan to implement AI so Mindar can accumulate unlimited knowledge and speak autonomously. We also want to have separate sermons for different age groups to facilitate teachings,” Goto said.

Mindar, a humanoid Buddhist deity, makes hand gestures to imitate human-like dialogue during sermons in Kyoto, Japan.

Kodaiji Temple

Regarding possible concerns that a robot deity could be considered sacrilegious, Goto was firm in his stance that Buddhism was about following Buddha’s way, not worshiping a god.

“The Buddhist goddess of mercy, Kannon, can change into anything. This time, Kannon was represented by a robot,” he said.

Mindar epitomizes the ubiquity of robots in daily life in Japan, which produces 45% of the global robot supply, according to the International Federation of Robotics.

“We Japanese are very positive about accepting robots. If other countries recognize that it’s very convenient, they will use it too, even in religious fields,” Ishiguro said.